When you think of deadly animals, it's easy to think of creatures with sharp teeth and claws, or with fangs and venom. You might not even think of mosquitoes at first. But mosquitoes are the deadliest animal on the planet. This is due to the diseases they spread. Over 700,000 deaths are caused each year by these diseases through mosquito bites.

Many strategies are used to try to reduce the spread of disease by mosquitoes. Each of us can reduce bites with clothing, mosquito nets, and changes in our behaviors. But there are other tools that people or researchers can also use to fight mosquitoes. First, we can reduce habitats where eggs can be laid to try to keep numbers low. However, often this is not enough. One of the main other tools we can use are chemicals called insecticides. Another new tool is genetically modified organisms (GMOs), which you may have heard before in the grocery store. Finally, we can use the natural enemies of mosquitoes to eat mosquito larvae.

Reduce habitat to fight mosquitoes

The main way to fight mosquitoes is to reduce the habitat where they breed. This is something you can help with too! Mosquitoes can breed in small, large, clean, or dirty bodies of water. The preferred type of water depends on the species. Adults lay eggs on or near these water sources and then the larvae and pupae live within the water until they emerge as adults.

If these water sources are reduced, then the number of mosquitoes should also be reduced. These habitats can be reduced by filling in holes, ditches, or ponds that hold or collect water. Containers that hold water can also be dumped or removed. Always make sure to check your surroundings for items that can collect water and remove those that you can. Encourage your neighbors to do the same. Any breeding sites that can’t be filled in, covered, or dumped can be treated with other methods.

Insecticides can kill or deter mosquitoes

Insecticides are one of the most commonly used tools to reduce mosquito numbers. Many can kill mosquitoes and some can stop mosquitoes from biting you. Some insecticides are used in the home, sprayed on walls and bed nets. Others are used outside on crops, land, and homes.

These chemicals work by killing mosquitoes or make them avoid the area. However, this does not always happen. In the last few decades, the chemicals we use have started to kill fewer mosquitoes than before. The chemicals haven’t changed, but the mosquitoes have. Over generations, the genes of mosquitoes can change. Those changes may let some of the mosquitoes avoid certain effects of such chemicals. This type of change is called insecticide resistance. The genetic changes can then be passed on from one generation to the next.

When the same chemical is used in an area for months or years in a row, there will likely be more and more mosquitoes with this change. But, we can use chemicals in a different way to try to prevent this from happening. For example, we can use them in a combination or in a rotation treatment. In combination treatments, we use two or more insecticides at the same time. With rotation, we switch back and forth between two or more chemicals for each treatment. This will make it more difficult for mosquitoes to survive. These are just two of the strategies that can help reduce the chance of resistance.

Mosquito GMOs

Another way to lower mosquito numbers is by genetic modification. Modification can be made to the genes of mosquitoes. A mosquito with changed genes would be called a genetically modified organism, which is also known as a GMO. One of the main ways to modify mosquitoes is the sterile insect technique (also known as SIT). Another way is to infect mosquitoes with bacteria called Wolbachia.

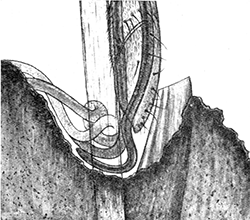

The sterile insect technique (SIT) only modifies the male mosquitoes. The male mosquitoes are modified so that they are sterile (hence the technique’s name) and cannot reproduce. The females that mate with sterile males won’t produce any offspring. If enough sterile males mate with females, then the next generation should be smaller. Males that are not sterile that mate are responsible for the new population. Many sterile males need to be released into the environment (often more than one time) for this method to have an impact.

Wolbachia is a type of bacteria found within some mosquitoes, but it is not found within Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. When female Ae. aegypti are infected with this bacteria, they are less likely to spread disease to humans. This is due to the bacteria competing with the viruses that cause disease. Wolbachia also affects male sperm, and actually prevents eggs from hatching when the mating males are infected. This reduces mosquito populations. When both sexes are infected and mate, this bacteria can be passed on to the next generation. When this happens, both males and females in the next generation will have the same issues as their parents. This method does not yet work for all mosquito species, but scientists are trying to make it work for other mosquitoes too.

Mosquito predators

Mosquitoes can be killed by their natural predators. Two of the most common mosquito killers are a type of bacteria and a fish. The bacteria is called Bti for short, and the fish is called the mosquitofish.

The full name of the bacteria Bti is Bacillus thuringiensis, and it's the subspecies israelensis. It naturally occurs in the soil and produces toxins that kill larvae. Bti is made in liquid or tablet forms for pest control to use in natural or man made water sources. It is toxic to all mosquitoes and because of that, it can be used worldwide.

Mosquitofish are small, freshwater fish that eat mosquito larvae (which is how they got their name). Their scientific name is Gambusia affinis. They are not the only fish that feed on mosquito larvae, but they are the most commonly used fish for mosquito control. These fish can be placed in natural or artificial water sources. By eating the larvae they help reduce the number of mosquitoes that become adults. This will help to reduce mosquito population size.

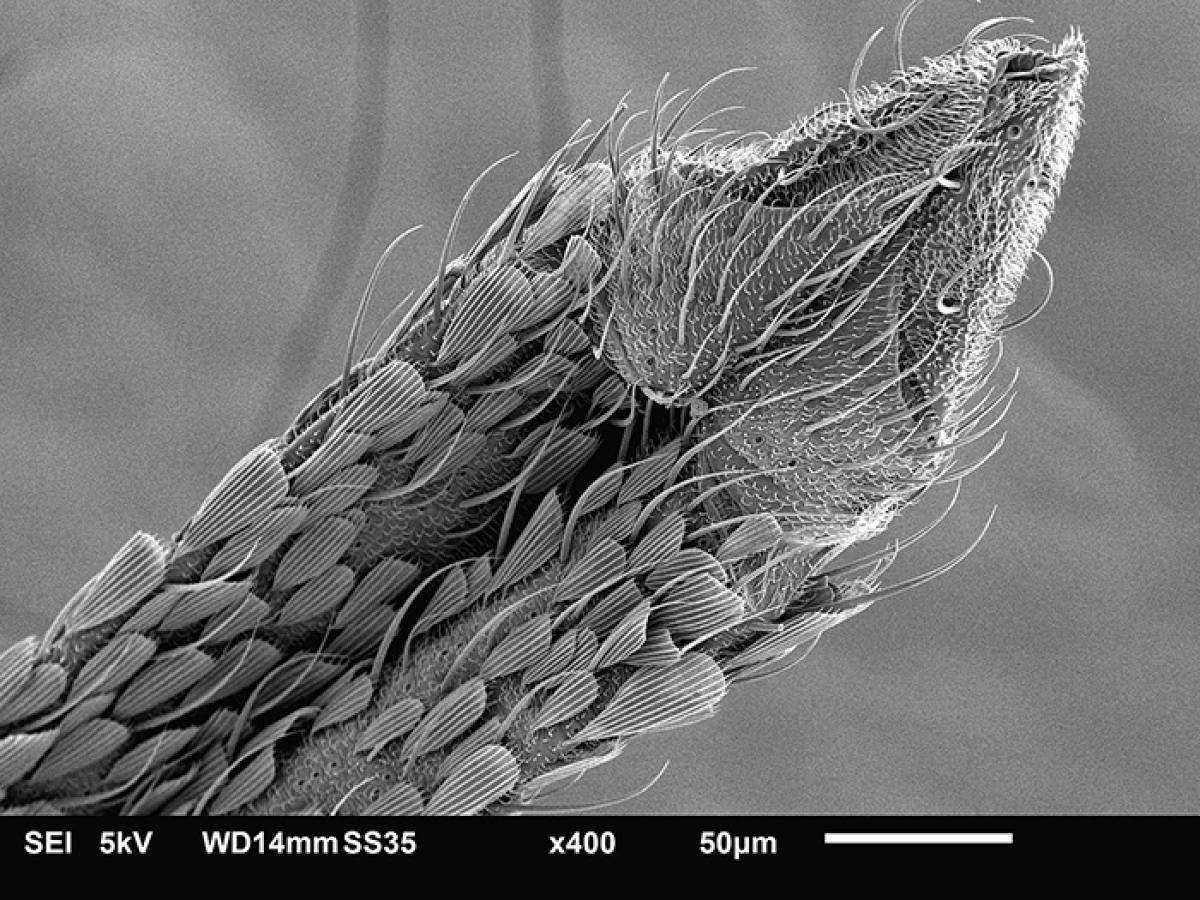

Additional images via Wikimedia Commons. Scanning electron microscope image of mosquito proboscis by Judyta Dulnik.

Read more about: All About Mosquitoes

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Fighting Mosquitoes

- Author(s): Dr. Biology

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published: 11 Aug, 2022

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/fighting-mosquitoes

APA Style

Dr. Biology. (Thu, 08/11/2022 - 16:24). Fighting Mosquitoes. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/fighting-mosquitoes

Chicago Manual of Style

Dr. Biology. "Fighting Mosquitoes". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 11 Aug 2022. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/fighting-mosquitoes

Dr. Biology. "Fighting Mosquitoes". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 11 Aug 2022. ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/fighting-mosquitoes

MLA 2017 Style

This tiny body part, a proboscis, enables infected mosquitoes to spread disease. What are the best ways we can fight mosquitoes on a larger scale?

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.