Tracking the Invisible

If you look at a stretch of hot, open desert, you can’t imagine anyone calling it home. But soil specialist Professor Ferran Garcia-Pichel arrives at the scene equipped with forensic investigation tools. His goal—make the invisible visible!

Just like a crime scene investigator, he knows that all living things leave behind hidden tracks. To find out who has been sitting in his soil he has his two modus operandi—methods of operation—to uncover the inhabitants’ identities.

Gather the Evidence

First gumshoe solution: gather indirect evidence. To protect themselves from the harsh UV rays of the unrelenting sun, desert microbes produce sunscreen. This defensive mechanism causes them to shapeshift. They change their color. By looking at photos of the earth taken by space satellites, super sleuth Garcia-Pichel can pinpoint where to dig for dirt. Armed with a wide-brimmed hat, a shovel, and specimen containers, he can collect samples of microbes and bring them back to the lab.

Once back in the lab, Garcia-Pichel and his team of investigators attempt to grow the microorganisms in the lab to investigate their behavior and determine the species. But many refuse to grow in this strange, new environment, so Garcia-Pichel must resort to other means of identification.

Forensic Analysis

Second sneaky method of detection: forensic analysis of the crime scene. All forms of life, including you and me, carry instructions on how to make copies of ourselves. This important information—our genetic identity—is stored in code, a cryptic message written in nucleic acids.

To collect DNA from people, forensic scientists usually collect a cheek swab. Garcia-Pichel uses the same techniques, but instead of a cheek swab, he uses a small sample of soil.

From a cheek swab, the majority of the DNA will be from the tested individual. A few fragments of code from the microorganisms living in your mouth might sneak in, but they can be recognized and quickly discarded. But with a soil sample, you have a messy mixture of bits and pieces from lots of different living organisms all thrown together in a big, muddled brew—what scientists neatly term a “heterogenous” mix.

Finding the Needle in a Haystack

Imagine walking into a library in search of a single book. Normally you could walk over to the computer catalog, type in the author’s name or book title, and the computer would tell you precisely where to go to pull that exact book off the shelf. If a tornado came through and knocked all the books off the shelves, swirled them around into a big chaotic jumble, ripped off the covers and threw the pages up into the air and then let them all swirl back down into one gigantic pile, you would have trouble finding a specific book.

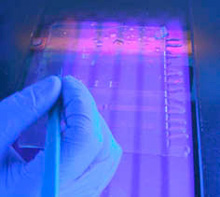

To make sense of his soil samples, Garcia-Pichel must sift through such an unruly jumble of information—a task much more complex then dusting for fingerprints. However, he does have help. Forensic techniques help him disentangle the mess and find the hidden gem in the giant pile of debris. Scientists invented a technique called Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR), a nifty means of making a lot out of a very little. Instead of amplifying the whole swirl of genetic information, scientists use PCR to magnify just the bits of information they need.

Using special hooks called primers, scientists go fishing in the jumbled sample for the genetic information they want. Let’s go back to our disorderly pile of pages from an entire library. Maybe you want to collect all the pages that mention Harry Potter. You could sit there for days on end, reading over every page to see if it mentioned the boy wizard. After a few hours, your eyes would start to get buggy and the text might blur. Soon you would be so frustrated, you would call it a day.

Primers magically find every single page that mentions Harry Potter and make oodles of copies, so that they rise to the top of the pile and you can see them easily. Scientists can design primers to pull out genetic information on any subject of their interest. They can even design a primer that hones right in on the identity of the organism, much like the title page of a book. This special primer finds all the different copies of a specific gene, the 16S ribosomal RNA gene. This gene is highly conserved, which means a version of it exists in almost all microorganisms.

By looking at the slight differences in the photocopied versions of this conserved gene—much like performing a police line-up and comparing them to mug shots of known criminals—Garcia-Pichel can figure out who was living in his soil sample.

Read more about: Sonoran CSI

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Tracking the Invisible

- Author(s): Dr. Biology

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published: 10 Dec, 2010

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/tracking-invisible

APA Style

Dr. Biology. (Fri, 12/10/2010 - 09:54). Tracking the Invisible. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/tracking-invisible

Chicago Manual of Style

Dr. Biology. "Tracking the Invisible". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 10 Dec 2010. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/tracking-invisible

Dr. Biology. "Tracking the Invisible". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 10 Dec 2010. ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/tracking-invisible

MLA 2017 Style

Microbiologist Ferran Garcia-Pichel studies the microscopic world just below the desert surface. Listen to his podcast "You Say Dirt, I Say Soil" to get all the dirty details.

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.