Pleistocene Rewilding

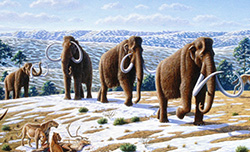

You are bundled up in Siberia, gazing across the fields of melting snow, and large fuzzy elephant-like beasts move across the landscape. You watch them and realize they look like mammoths, which are supposed to be extinct. Your mouth drops open as you look at their giant tusks. The stomp on by, not paying any attention to you, slowly grazing as they go along, trampling the ground. You think to yourself, “what are these mammoths doing here? This is so cool!”

Pleistocene rewilding is an idea that has been proposed for all sorts of areas across the world. This type of rewilding isn’t just about the Pleistocene, despite its name. It can also involve species from other time periods (or, more accurately, epochs) as well. This is a highly controversial idea that made a big splash when it was proposed. The idea is to bring back animals similar to extinct animals including in some cases animals that have been extinct for a long time.

Why is this something that scientists are interested in? Well, some of those animals might fill in gaps in certain ecosystems. For example, if an ecosystem used to have a top predator that went extinct, maybe a similar predator could fill that role. This has been proposed with endangered animals that might do well in other places. There have been ideas of bringing African lions to North America since there was once an American lion. This would help support and grow African lion populations since they would have a new space to roam. Another reason is to give the animals a place to live if their habitat is gone. Recently extinct animals may have gone extinct because of habitat destruction. Some people think introducing them into new habitat could help fix this problem. There is a lot of push back over this idea. Not all people are keen on the idea of introducing large predators in places close to where they live.

De-extinction: Bringing Back the Dead

There are a few different ways scientists might try “de-extinction.” The common way proposed to bring back a species is by combining its DNA with the DNA of a closely related species. This would be done using recently developed tools. For example, CRISPR Cas9. One of the more far-out proposals of this kind of rewilding is to try to bring back long extinct species.

Scientists can breed current species to create an animal that is close to one who went extinct, such as using closely related living tortoises to bring back the Pinta Island tortoises. The Pinta Island tortoises went extinct in 2012. The last tortoise of this species was Lonesome George. The Pinta Island tortoises were thought to be extinct in the early 20th century. But George was discovered in the 1970s, the last of his species. When he died he was estimated to be over 100 years old. George only died in 2012, so the Pinta Island tortoises might still fill a place in their former ecosystem. This method might also be useful for other species, like the passenger pigeon.

Another way is by bringing back long dead animals. For example, there was a proposal to bring a hybrid of the woolly mammoth back and put it in Siberia. Woolly mammoths lived in the tundra during the last ice age. The tundra stretched from northern Asia, through parts of northern Europe, and across the northern part of North America. The scientists thought introducing the woolly mammoth in Siberia would be a good way to trap carbon in the ground. The mammoth hybrid would do this by trampling the ground. By compressing soil, the things that are in the soil are kept there, including gases like carbon. Soil has a lot of carbon in it. So, carbon couldn’t easily escape in the air. Trapping carbon in the soil helps to reduce climate change by keeping it out of the air. Carbon is a greenhouse gas that contributes to the warming of our atmosphere. However, if scientists bring back an animal like the woolly mammoth there are added problems. The ecosystem in which it lived is gone, and it might not survive in Siberia now.

The Past and Future of Pleistocene Rewilding and De-extinction

Bringing back species can be complicated. It is more complicated if their habitat no longer exists. It is a tool that is being developed to return iconic species to their ecosystem. Or to use species as proxies for extinct animals. Conservationists see it as a way to return lost species to ecosystems. They also see it as a way to correct all the extinctions that have happened due to humans. Like the passenger pigeon that went extinct in the early 1900’s due to hunting and habitat destruction.

While natural rewilding and reintroductions are ongoing, Pleistocene rewilding and de-extinction are topics that are only theoretical right now. Scientists haven’t done them yet, but are working toward that goal. The cost and unknown outcomes make them risky ideas. Some species might still have a place in their former ecosystems. However, if the thing that caused them to go extinct is still an issue, then the species could die off again. So, these species might not survive now without other large changes. There are also moral objections to creating animals and introducing them into areas. Either way, this process would be very expensive and take a lot of time, planning, and research. It might be worth it, though, if it produces new ideas for combating greenhouse gases, such as by using the tramping power of the woolly mammoth.

Sabertoothed-cat skull image by Jebulon via Wikimedia Commons.

Read more about: Where the Rewilded Things Are

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Pleistocene Rewilding and De-Extinction

- Author(s): Challie Facemire

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published: 28 Mar, 2020

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/pleistocene-rewilding-and-de-extinction

APA Style

Challie Facemire. (Sat, 03/28/2020 - 07:42). Pleistocene Rewilding and De-Extinction. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/pleistocene-rewilding-and-de-extinction

Chicago Manual of Style

Challie Facemire. "Pleistocene Rewilding and De-Extinction". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 28 Mar 2020. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/pleistocene-rewilding-and-de-extinction

Challie Facemire. "Pleistocene Rewilding and De-Extinction". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 28 Mar 2020. ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/pleistocene-rewilding-and-de-extinction

MLA 2017 Style

This is the skull of Homotherium crenatidens, better known as a saber-toothed cat. Saber-toothed cats lived in the Pliocene and Pleistocene epochs. They died off about 12,000 years ago during the Quaternary extinction.

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.