Illustrated by: Denise Inguito

Have you ever seen a magic trick? A popular trick is watching a magician pull a rabbit out of a hat. First, the magician sets a top hat on a table. Then, with a tap of the magician’s wand, presto! The rabbit appears, to the delight of the audience.

Humans have been making rabbits appear for a while. Rabbits never lived in Australia until humans brought them there. In the 1800s, a British settler missed hunting rabbits, so he imported some and set them loose. “Pretty soon, his estate was full of rabbits eating things, and he had lots to shoot and he was happy as a clam,” said Grant McFadden, an ASU scientist.

Then, poof! The rabbits did what they are best at—they bred like crazy. Without any predators, the rabbits spread. “By about 1950, there were billions of them hopping around in Australia,” McFadden said. Rabbits are herbivores, so they only eat plants. They ate all the crops and outcompeted other animals for food, becoming a true Australian pest.

Australians tried all sorts of tricks to stop the rabbits. First, they tried to hunt the rabbits with guns and traps, but that didn’t work. Next, they tried to build a rabbit-proof fence, but that didn’t work either. Nothing worked until they turned to biological warfare.

In the 1950s, scientists unleashed a virus to tame the wild rabbit population. This virus is very good at one thing—killing almost all of the rabbits it infects. Rabbits are all around us, but most people are not familiar with this virus. McFadden studied this virus for most of his career.

Unpacking a Rabbit Virus

The myxoma virus is unusual because it only affects rabbits. It is harmless in other animals like mice and humans. It invades rabbits’ cells, takes them over and spreads itself quickly. Most rabbits die within 14 days of getting infected. When Australia used the virus, it worked really well. It reduced the rabbit population from over a billion to 100 million in just two years.

“I was really interested in how the virus causes disease, and also why is it restricted to rabbits,” McFadden said. “I eventually settled on this virus because nothing was known about it.” Scientists understood that it killed rabbits, but no one had researched its molecular biology.

McFadden spent a lot of time figuring out how the virus works. Now he wants to use what he learned for what may be the ultimate medical magic trick: a new treatment for people with cancer. His goal is to use the virus as a new tool to help the human body detect and kill unwanted cancer cells.

Giving a Virus to Cancer

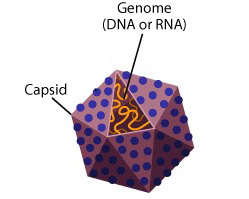

Viruses are small, but they pack a big punch. They are made of two main parts: a hard, outer protein shell, which protects its inner cargo of DNA. The virus DNA has just 159 genes. That is a lot less than human DNA, which has about 20,000 genes. About half of the virus genes are dedicated solely to dodging the immune system of rabbits.

The life cycle of a virus starts when it bumps into a cell, McFadden said. The virus grabs on to the surface of the cell, gets inside and fights the cell’s defenses that come from the immune system. If it can defeat them, it starts making copies of itself. It pops out fresh virus on the other end. This kills the cell, and the virus goes on to infect other cells.

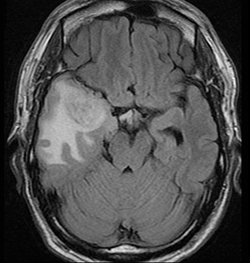

McFadden noticed something unusual about myxoma virus. “In the lab, the virus will grow in all rabbit cells and has trouble growing in the normal cells of mice or humans. But if you take a cancerous mouse or human cell and put the virus on it, it grows in those pretty much like in a rabbit,” he said. “When this virus is in tumor cells, it thinks it’s in a rabbit. It’s not... We started wondering, could we use this virus to actually treat cancers in mice and humans?"

Building Cancer Treatments

Cancers are very sneaky. Just like the rabbit population in Australia, cancer cells can grow out of control and spread quickly throughout the body. They can make people very sick. Cancer cells avoid detection by their host’s immune system. This is because that immune system’s job is to try to destroy the cancer.

But many cancer cells have an “Achilles heel”—they have a big weakness that makes them vulnerable to being killed. To become cancer cells that grow out of control, normal cells also lose their defenses against infection by microbes. This means they can be infected by the myxoma virus.

McFadden’s goal is to take the myxoma virus from rabbits and use it to kill cancer cells in humans. For about ten years, he has tested this idea in animals. It was good at infecting and killing cancer tumors in mice. He thinks the virus could be safer than other cancer treatments. Because it only grows in rabbit cells or cancer cells, it would not infect healthy human tissue.

He wants to start testing the treatment in humans soon. McFadden said he hopes to get myxoma virus into human clinical trials in the next few years. About two dozen other viruses that might treat cancer are currently in clinical trials. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the first virus to treat cancer in 2015.

For a little while, scientists thought these viruses could be like a silver bullet against cancer, but the treatment is not perfect. To make it more effective, McFadden and other scientists want to pair it with other cancer treatments. The idea is still to infect cancer cells with a virus. The virus would help the body’s immune system recognize and then destroy the infected cancer cells.

Treating cancer, a major pest among human diseases, might just be the ultimate act of pulling a rabbit out of a hat.

Treating Cancer with a Rabbit Trick was created in collaboration with The Biodesign Institute at ASU.

Read more about: Treating Cancer with a Rabbit Trick

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Treating Cancer with a Rabbit Trick

- Author(s): Ben Petersen

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published: 3 Apr, 2018

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/meet-our-biologists/cancer-rabbit-trick

APA Style

Ben Petersen. (Tue, 04/03/2018 - 12:49). Treating Cancer with a Rabbit Trick. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/meet-our-biologists/cancer-rabbit-trick

Chicago Manual of Style

Ben Petersen. "Treating Cancer with a Rabbit Trick". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 03 Apr 2018. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/meet-our-biologists/cancer-rabbit-trick

Ben Petersen. "Treating Cancer with a Rabbit Trick". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 03 Apr 2018. ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/meet-our-biologists/cancer-rabbit-trick

MLA 2017 Style

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.