Illustrated by: Megan Joyce

A hen moves nervously around the yard, walks through a small door into her coop, and lays down in her nest. Within a few minutes, she has laid an egg. A chicken egg is a huge single cell, and soon it will develop into a baby bird. So, how did the hen make this egg that will become a living, breathing animal? Or in case of plants, how are seeds made? The ways in which life on earth creates new life is something that we call “reproduction.”

Some parts of reproduction are similar not just in plants and animals, but in all organisms, including single-celled ones. Organisms reproduce either with a partner (sexually), or alone (asexually), or both ways, depending on the species. In any case, genetic information in the form of DNA is always passed down from the parent or parents to the next generation. DNA is like a set of instructions for how to make a body and how to keep it working. That’s why human babies look so much like their parents – they have a mix of their parents’ DNA, and so they were formed using a mix of their parents’ instruction sets.

Mixing Genes with Sexual Reproduction

In sexual reproduction, it usually takes two parents to make an offspring. If you look around, most of the plants and animals you know, including humans, reproduce sexually. One of the main points of sexual reproduction is that some of each parent’s genes are mixed together to create a new pattern of genes. This helps the offspring deal with the world in a new way.

The first step of sexual reproduction is called meiosis. In meiosis, a cell with a full set of genes duplicates its DNA, then divides into four cells with half a set of genes in each cell. These special cells that have half of the genetic material of a regular cell are called haploid cells (hap sounds a bit like half, right?). A cell with the normal amount of genetic material is called a diploid cell (this sounds a bit like “double”). In animals, haploid cells are only made in the testes in males and in the ovaries in females.

The second step of sexual reproduction is gamete fusion. A gamete is a haploid cell that can fuse with another haploid cell to make a new diploid cell. Usually, gametes from two different individuals fuse together. In organisms with different sexes, males and females make different kinds of gametes. The male gamete is called a sperm; they’re small, swim around, and often look like tadpoles. The female gamete is called an egg and it is much larger than the sperm. The egg isn’t able to swim around like the sperm, and instead it waits for sperm to find it. This is likely because it has to hold a lot of energy, so it is built for storage instead of movement. It has more cytoplasm, and sometimes even has yolk. Yolk provides food for a developing baby.

Plants do things a little bit differently. In plants, haploid cells called pollen are made in the flower’s anthers, and haploid cells called ovules are made in the flower’s ovary. Some plants make both pollen and ovules in one flower, and other species have separate male and female flowers, or sometimes separate male and female plants. A haploid pollen grain travels to an ovule through air, water, or by catching a ride on an animal. Cells in the pollen grain and ovule then divide again to make plant sperm or egg cells. Fungi are also very different, and only some fungi mate. Fungi don’t have sperm or eggs, but haploid cells can fuse to make diploid cells.

Copying Yourself with Asexual Reproduction

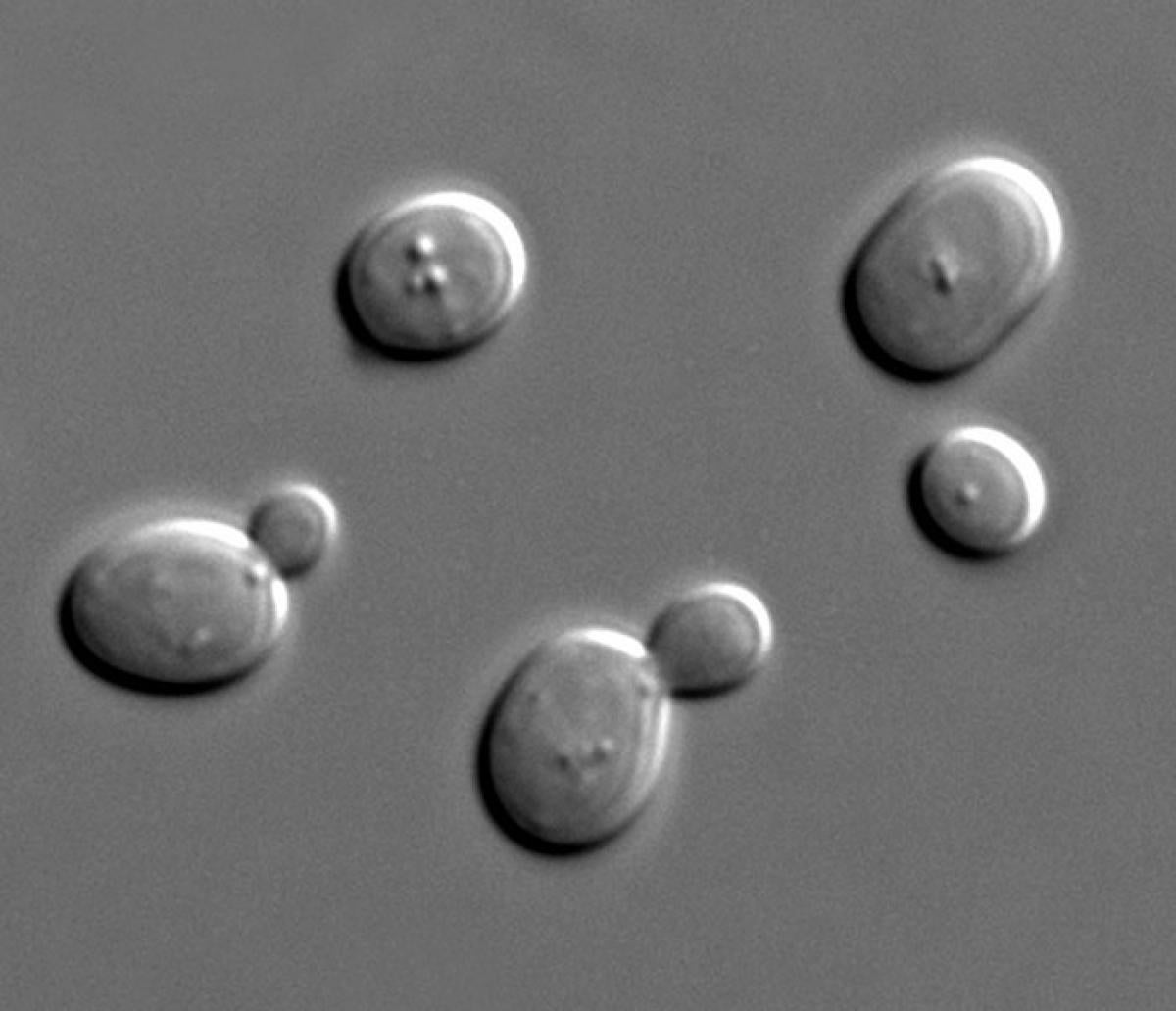

Yeast is a unicellular organism that you may be familiar with. This is one organism that we use in our food a lot. It is what makes bread rise and it ferments sugars in some drinks like Kombucha tea. Yeast is a fungus that can reproduce sexually, by forming haploid spores that combine with other spores. But yeast often reproduces without forming spores, through a process called budding. Budding is when a “parent” yeast cell grows a new “daughter” cell as a small, round bud. Once it’s ready, this daughter cell pops off, grows to full size, and lives on its own. In budding, the daughter cell receives a copy of the parent cell’s full set of genes. This way of making new life is an example of asexual reproduction.

Another way to reproduce asexually is with “parthenogenesis,” where an egg grows into a plant or animal without fusing with sperm. Other asexual organisms may use fission or fragmentation. Fission is when an organism purposefully splits its body in two. Fragmentation is when part of a body breaks off, and can form a new body.

In asexual reproduction, the DNA for a new organism comes from a single parent. DNA in the new cell is identical to the DNA in the parental cell, unless there is a mutation. This, or a similar process, is the main way most unicellular organisms like bacteria and amoebas reproduce. Certain plants like strawberries reproduce asexually too. Some invertebrates can also reproduce asexually, like some species of starfish, worms, and some insects. Amongst vertebrates, some fish, some whip tail lizards, and some snakes use asexual reproduction.

Asexual reproduction has a huge benefit, in that a big population can arise from a single parent very quickly. But there are some drawbacks to this. The similarity of DNA between individuals in a population of clones can make it easier for these species to be wiped out by diseases.

Additional images via Wikimedia Commons and PIxabay. Budding yeast by Masur.

Read more about: To Breed or Not to Breed

Bibliographic details:

- Article: To Breed or Not to Breed

- Author(s): Sarala Pradhan, Ioulia Bespalova

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published: 12 Jul, 2019

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/reproduction-types

APA Style

Sarala Pradhan, Ioulia Bespalova. (Fri, 07/12/2019 - 09:25). To Breed or Not to Breed. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/reproduction-types

Chicago Manual of Style

Sarala Pradhan, Ioulia Bespalova. "To Breed or Not to Breed". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 12 Jul 2019. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/reproduction-types

Sarala Pradhan, Ioulia Bespalova. "To Breed or Not to Breed". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 12 Jul 2019. ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/reproduction-types

MLA 2017 Style

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.