Illustrated by: Sabine Deviche

A human cell – or any other cell ‐ is like an old watch: full of cogs that have to be exactly the right shape and size in order to make the watch work. If a cog has a small crack or only one tooth is missing the watch may still work.

However, if the teeth would suddenly get a different shape the whole system would break down and the watch would stop ticking. Proteins are the cogs of living cells. As long as they have the right shape, they can work together with the other proteins to keep the cell healthy. Yet minor changes in shape may be enough to disrupt the cell and that can cause diseases like early aging and cancer.

Scientists like Jan Pieter Abrahams in Leiden want to know exactly what proteins look like. Just like new movies or video games, they also want to see the proteins in 3D. If they know their 3D shapes, they can think of a way to correct changes in their shape that lead to diseases. However there is a problem - they have to be able to see the tiny of parts that make proteins. They need to see atoms. To do this they use a special way of seeing things as small as atoms. They use X-rays to look inside crystals made of the proteins.

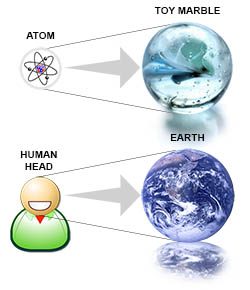

How Small Are Atoms?

As Jan Pieter explains, “If you would enlarge an atom to a marble, this would be like enlarging your own head to the size of the earth.” You can imagine that it’s not possible to see the detailed shape of single proteins with just your eye or even with a microscope. Therefore scientists have come up with another method to make the proteins visible. They start by making crystals from the sample they want to learn about.

Anatomy of Crystals

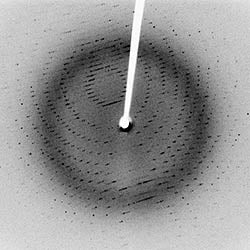

Protein crystals are three-dimensional blocks of regularly ordered proteins. If scientists shoot an X‐ray beam at a crystal, the X‐rays are scattered into many different directions that make a very unique pattern. This is called a diffraction pattern and can be transferred on the fly to a computer using a digital detector. Scientists have made special software that allows them to use the diffraction pattern and build a 3D shape of what the protein should look like.

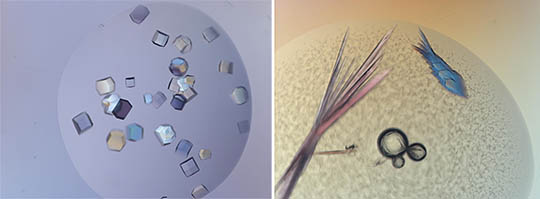

Making crystals is an art in itself. For every protein, a scientist has to find out what conditions this protein needs to grow into a crystal. This can be a certain combination of substances, a certain size of the drop of liquid, or even a bit of dust or hair. Scientists experiment using many different ways that have worked for other proteins in the past. Sometimes it takes years before they finally have a crystal. The chances that a protein will form a crystal are small. 92% of all proteins never form a crystal, even though scientists try thousands of different conditions.

When proteins do form crystals, they sometimes make funny shapes like the little man and the fish. This does not happen often, but are fun to look at when they do occur. Our tiny crystal man and fish did not give new results about the shape of proteins, but they are fun to enjoy for their beauty and shape.

There have been some very famous X-ray diffraction experiments. One was done by, Rosalind Franklin, a scientist working with samples of DNA. It was one of her photographs that provided important information about the structure of DNA. At the time she made this photograph there were many ideas about the shape of DNA. Many scientists were trying to figure out its shape and how it worked. There were bits and pieces of information and scientists were trying to piece together the information - it was very much like a scavenger hunt only for biologists and biochemists. Rosalind Franklin's now famous Photo 51 was one of the key pieces that showed DNA had a special shape - a double helix that was only confirmed using X-ray diffraction.

About the author: Martine Oudenhoven graduated as a biologist from Wageningen University, The Netherlands. Now she works as a communication specialist to improve knowledge exchange in and about this field. She is fascinated by how scientists use technology to make things visible that cannot be seen with the naked eye. Ms. Oudenhoven has also been a frequent volunteer translator of Ask A Biologist content.

References:

Rosalind E. Franklin and R.G. Gosling (1953) Molecular configuration in Sodium Thymonucleate, Nature vol. 171, p. 740

J.D. Watson and F.H.C. Crick (1953) A structure for Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid, Nature vol. 171, p. 737

Personal communication:

Professor J.P. Abrahams, Biophysical Structural Chemistry, Faculty of Science, Leiden University

Igor Nederlof, Biophysical Structural Chemistry, Faculty of Science, Leiden University & Yoshitaka Hiruma, Protein Chemistry, Faculty of Science, Leiden University

Additional images from Wikimedia.

Read more about: Making Life Crystal Clear

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Making Life Crystal Clear

- Author(s): Martine Oudenhoven

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published: 19 Aug, 2012

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/making-life-crystal-clear

APA Style

Martine Oudenhoven. (Sun, 08/19/2012 - 09:36). Making Life Crystal Clear. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/making-life-crystal-clear

Chicago Manual of Style

Martine Oudenhoven. "Making Life Crystal Clear". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 19 Aug 2012. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/making-life-crystal-clear

Martine Oudenhoven. "Making Life Crystal Clear". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 19 Aug 2012. ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/making-life-crystal-clear

MLA 2017 Style

A crystal of Bence Jones protein created for X-ray crystallography, which can reveal detailed, three-dimensional protein structures. This protein is sometimes found in the urine of people with certain cancers.

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.