Illustrated by: Brendan Koehler

Frozen Life

Across the globe, the oceans seem to have pretty strong similarities. They are huge, deep, and salty. But before you try to add "they don't freeze" to your list, let's take a look at the Arctic Ocean.

The Arctic is an ocean in the northern-most part of the world. Near the North Pole the ice stays frozen year after year. We call this multiyear ice. In the coastal areas the ice melts every summer. We call this first-year or land-fast ice.

What's even more surprising is the number of small organisms that we can find living in the ice.

The Arctic ecosystem is home to many organisms, from microscopic bacteria, phytoplankton, and algae, to large animals like whales, polar bears, and even humans. In the spring and summer many birds and animals migrate to the Arctic to take advantage of the large amount of food available.

On land in the Arctic (in northern Canada, northern Alaska and Russia, for example), there is not very much plant life because it can't grow through the frozen soil. Sometimes the ground permanently freezes below a shallow depth, making what we call permafrost. Only plants with shallow roots such as tundra grasses and mosses can grow here. There are no trees, cacti, or other larger plants found in the Arctic. Therefore, the base of the food web comes from either grasses or from the phytoplankton in the ocean.

Mighty and Miniature

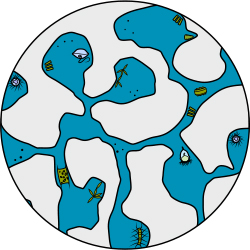

Phytoplankton are really tiny. So tiny in fact, that you usually need a microscope to see them. While you might think that a tiny organism isn't very important, that definitely isn't the case.

The phytoplankton serve as a base of the food web. They are typically found in the water but since the Arctic Ocean is covered by ice for most of the year they are also found inside the ice. When inside the ice, the phytoplankton are called sea ice algae.

The sea ice algae are eaten by grazers such as zooplankton (either single-celled or multi-celled organisms that are not plants) for their own nutritional needs. In the Arctic food web, some whales have special teeth called baleen. These teeth let them feed on the zooplankton by filtering plankton-rich seawater.

Humans in the Arctic?

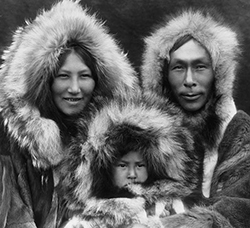

The people from the North Slope of Alaska are called the Iñupiat. These people in the Arctic are allowed to harvest, or take from the ocean, a certain number of Bowhead whales each year. This is an important part of their life and culture.

For many generations, they have depended on the whales for food. In remote areas of Alaska you can’t always run to your local grocery store for food, because groceries have to be flown in and they are expensive. So the local Inupiat people continue to hunt for survival. They only take what they need and they use the entire animal so they are not wasteful.

Back to the Base (of the Food Web)

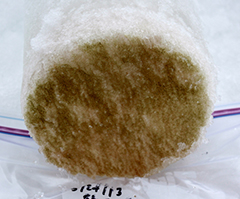

In the fall, the temperatures drop and the ocean begins to freeze. As it freezes, freshwater ice forms and concentrated salt water gets left behind and forms pockets of salt water called brine pockets. Phytoplankton living in the open water can get trapped in these brine pockets and end up staying in the ice all winter.

There is too little light for photosynthesis during the winter in the high Arctic so the plankton are not able to grow. This makes food harder to find. A lot of the animals living in the Arctic either hibernate for the winter (like polar bears), or migrate south (like Caribou and birds) to find food.

Waking Up Again

The algae begin to photosynthesize and grow again once sunlight becomes available in late winter. Without many grazers in the ice eating the algae, it grows quickly and becomes so dense that dark algal layers form.

The seawater is very rich in nutrients and can flush into the brine channels, supplying the sea ice algae with the nutrients needed to grow. Larger zooplankton such as copepods feed on the rich algal layers from underneath the ice.

Toward the end of spring, when the ice begins to melt, the sea ice algae are released from the ice and fall into the seawater or sink to the sea floor, where they are eaten by other animals.

This makes the algae (and the time they spend growing while trapped in ice) very important to the Arctic ecosystem. Without these phytoplankton, the waters wouldn't be able to support so many animals in spring.

This section of Ask A Biologist was funded by NSF Office of Polar Programs Grant Award number 1023140 as a part of Susanne Neuer's research.

Additional images from Wikimedia via Evadb (humpback whale), Keraunoscopia (Iñupiat family),and Patrick Kelley (Arctic ice).

Read more about: Frozen Life

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Frozen Life

- Author(s): Kyle Kinzler

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published: 9 Jul, 2014

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/frozen-life

APA Style

Kyle Kinzler. (Wed, 07/09/2014 - 11:31). Frozen Life. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/frozen-life

Chicago Manual of Style

Kyle Kinzler. "Frozen Life". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 09 Jul 2014. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/frozen-life

Kyle Kinzler. "Frozen Life". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 09 Jul 2014. ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/frozen-life

MLA 2017 Style

Small crustaceans such as this isopod roam around the ocean floor.

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.