Illustrated by: Sabine Deviche

It’s been happening for a while now. You’re restless and tired, you’re nervous around people, and you keep worrying you’re doing something wrong. Sometimes it gets so bad that you feel nauseated and go into a panic. Doctors can explain your symptoms—you may have an anxiety disorder. What doctors probably can’t explain is why 40 million people in the United States have anxiety, or why humans have anxiety in the first place.

Who might be able to explain that? Maybe a biologist who understands evolutionary medicine.

What is Evolutionary Medicine?

Evolutionary medicine uses what we know about evolution to improve understanding of our health, why we get sick, and how we can better prevent and treat disease. In case this seems a bit vague, let’s look at two specific examples of evolutionary medicine.

Examples of EvMed: Anxiety and Smoke Detectors

Let’s revisit the idea of anxiety. Does anxiety have any use? Well, it does sometimes. Anxiety is a defense that can protect us from potentially dangerous situations. If you are alone in the jungle and you hear a noise from an approaching animal, it may be “better to be safe than sorry” and respond to the noise by running away. This panic response may save you from hungry jaws. Being anxious or “vigilant” was likely very helpful to humans when we lived as hunter-gatherers.

Evolutionary Mismatch

Having this same response in today’s world could be called a “mismatch” between our behavior and the type of environment in which we now live. Mismatches can explain many disorders or diseases, as the speed of change in our cultures or environments can be faster than evolutionary change.

But in the case of anxiety, there must be selection to get rid of this over-response, right? Not really. The thing is, anxiety may be costly, but it can be very helpful, even today, and even in cities. It may make you more careful about locking up your valuables or staying out of dark alleys. Anxiety can keep you and your resources safe, so there is good reason to keep anxiety responses around.

No defense response is perfect though. Anxiety can be thought of as a response produced by a danger monitoring system. The problem with any monitoring system is that there can be false alarms. For example, if you’re frying food and the kitchen gets smoky, odds are your fire alarm will go off. It may be annoying to run around opening windows and fanning the fire alarm, but the alarm is there for a reason. The same is true of your personal danger monitor. It may go off at the wrong times. The “smoke detector principle” explains why false alarms are normal and expected in both systems. Viewing anxiety under an evolutionary lens may help people understand that this useful response was once vital to our daily survival.

Examples of EvMed: The “Old Friends” Hypothesis

Let’s go the opposite direction for the next example. Instead of talking about responses to danger, let’s talk about our “old friends”—parasites and bacteria! For much of human history, we lived in very different conditions. We had greater exposure to all kinds of microbes in the dirt, we spent time with animals most days, we didn’t have centralized bathroom systems, and we didn’t use medicines that destroyed microbes (antibiotics). Even just a hundred years ago, many humans lived with a variety of worms or parasites in their bodies, and were exposed to a wider variety of microorganisms. This is still the case in some societies today.

You might think, “well, isn’t it better that many of us live in cleaner conditions now?” This is true in some ways, but our immune systems don’t entirely agree. Our immune systems evolved in a more challenging environment. They fought to keep parasite numbers low, and to defend against a wider variety of bacteria.

Developments in medicine and sanitation today may at times leave our immune systems a bit… well… bored. Our immune systems don’t face the same challenges they once did, leaving them with less to do to keep us healthy. They also may not be as well programmed as they’ve been in the past, because they don’t encounter a wide enough variety of microbes early on. This may cause them to overreact and to attack our own cells. Self-attack is called autoimmunity and it’s a huge problem in a variety of diseases.

Autoimmunity is linked with diabetes type I, arthritis, multiple sclerosis, and maybe even cardiovascular disease. So we see the “old friends” hypothesis is another form of mismatch. We’ve created a new, cleaner environment, and our bodies haven’t been able to deal with the changes.

Can Evolution Help with Medical Treatment?

Ok, but can these evolution-based understandings of health help with medical treatment? Potentially, yes. For example, researchers are exploring whether treatment with parasitic worms can help people with certain autoimmune diseases. But the thing is, there is still so much more for us to understand. Ideas have to be brainstormed, past work has to be considered, and new experiments have to be designed, run, and analyzed. All these steps must happen before we can apply evolutionary medicine to current medical treatments. But, in some cases, and in some animal species, this new understanding is starting to help.

We are learning that diseases of the nervous system may be rarer in countries where parasite and bacterial exposure is still high. We are learning how antibiotic treatments and protocols might select for drug resistance in bacteria. We are learning that the age of parents may be linked to nervous system disease in their children. We are learning that treating bacterial infections with high doses of medicine may help drug-resistant bacteria, and that lower doses might better fight bacteria. And we are learning that breast milk is a personalized immune boost for babies.

The key here is that we are still learning. The field of evolutionary medicine is new and there is much to learn. But it’s worth pursuing because there are so many ways it can benefit us in the future. If you have a question about human medicine, it might be useful to try to use evolutionary ideas to help solve it. If Darwin were alive today, I think he’d be happy his theory of evolution has such potential to help people in their everyday struggles with health and disease.

Great research in evolutionary medicine is occurring at Arizona State University’s Center for Evolution and Medicine (CEM) and at a variety of institutions across the globe. The CEM is also working on a collection of educational resources that can be found at isemph.org/EvMedEd. For new updates on the field of evolutionary medicine, visit EvMedReview.com.

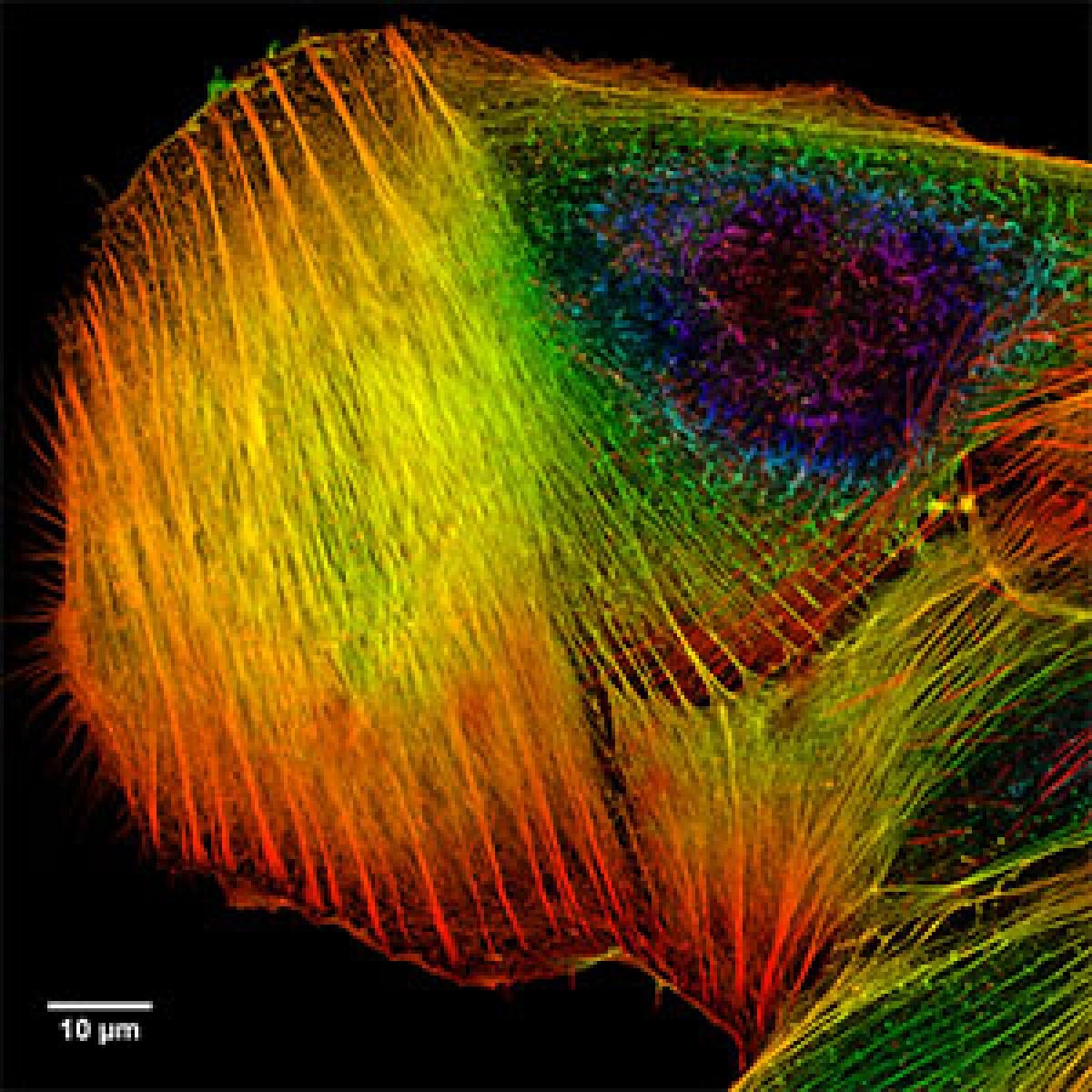

Stained osteosarcoma cell by Howard Vindin via Wikimedia Commons.

Read more about: What is Evolutionary Medicine?

Bibliographic details:

- Article: What is Evolutionary Medicine?

- Author(s): Karla Moeller

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published: 6 Jun, 2017

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/evolutionary-medicine

APA Style

Karla Moeller. (Tue, 06/06/2017 - 17:06). What is Evolutionary Medicine?. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/evolutionary-medicine

Chicago Manual of Style

Karla Moeller. "What is Evolutionary Medicine?". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 06 Jun 2017. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/evolutionary-medicine

Karla Moeller. "What is Evolutionary Medicine?". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 06 Jun 2017. ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/evolutionary-medicine

MLA 2017 Style

A bone cancer cell has been stained with color to show different parts of the cell. Why are humans so vulnerable to cancer? Evolutionary medicine may help us answer this question.

Explore recent research in Evolutionary Medicine with EvMed Edits.

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.