Animals of the Tundra

Could you handle always living in the cold? Some animals can. Animals of all sizes have adapted to harsh weather conditions and long winters of the tundra.

Many animals have shorter legs and ears to minimize exposing their skin to the cold. Some are also well adapted to living high up in the mountains. For example, mammals at high elevation are able to use oxygen more efficiently.

Small creatures, such as ground squirrels, can seek refuge in vegetation but because it’s usually sparse and low, it may expose them to predators. To avoid danger, some species have evolved to be fast runners or to be camouflaged.

Between summer and winter, the grayish-brown fur of snowshoe hare, arctic fox, and others like them blends into white hairs in preparation for winter camouflage.

Sometimes prey animals feed at night to avoid being eaten. They may also reproduce a lot since not all young will survive to adulthood.

Fat = Energy?

Another key to an animal’s survival in the tundra is knowing when to eat and when to sleep in order to save energy. Many animals in the tundra hibernate during the long, cold winter months.

Hibernation is a period of rest lasting several months. During this time, animals stay hidden in dens. Their metabolisms lower into a dormant state, so less energy is required for their bodies to perform the necessary functions. For that energy, they rely on stores of fat they built up over the summer.

Tundra animals have other strategies to keep warm too. It helps to have a lot of fur and fat. After all, the colder it is, the more energy it takes for a mammal to maintain a stable body temperature to live.

Just like in other biomes, in the tundra, different types of animals get energy from different types of foods. Carnivores are at the top of the food web because they are meat eaters.

Carnivorous mammals such as wolves and seals prey on smaller animals to survive while herbivorous mammals only consume plant-based foods. Animals that eat both other animals and plants are called omnivores.

Lemmings, voles, caribou, arctic hares and squirrels are examples of tundra herbivores at the bottom of the food web. They often have a strong sense of smell to help them find food underneath the snow.

Timing is Everything

Summer melts away the snow, allowing shallow wetlands to form. In the available pools of water, insects breed and attract birds. This explains why animals are most active in the short summer. They forage heavily on the plentiful insects and flowers that are in bloom before they are forced to hibernate or migrate to a warmer place for winter. Luckily, during the long-lighted days of summer, there is more time in each day to hunt for food.

Summer is for mating, too. Everything from insects, like mosquitoes, flies, moths, grasshoppers, blackflies and arctic bumble bees, to larger animals take advantage. It turns into a race against time.

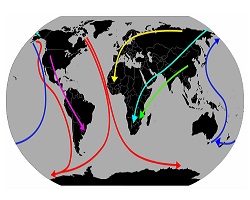

Migratory birds such as falcons, loons, sandpipers, terns and snow birds must successfully produce young during the short summer. If they don’t, there is not enough time to start over with a second nest.

Even given constraints like these, a lot of animals call the tundra home for at least part of the year. As the seasons change, so do the species found in the tundra.

Young plover, a kind of bird, are abandoned on the tundra in Alaska and have to make their way back to Argentina in South America on their own. The adult parents leave earlier, perhaps to allow more food for the young.

Stories like the plovers’ are normal for species that spend part of the time in the tundra.

Insect Anti-Freeze

Picture holding an insect in your hand and how tiny it looks compared to you and everything else. Even small insects live in the tundra. But how do they survive in below-freezing temperatures? For some, the answer is antifreeze.

If you’ve heard of antifreeze, it was probably from someone with a car. In cars, antifreeze is a manmade (and very dangerous) chemical mixture that allows all the water-based liquids to operate in a wide range of low and high temperatures.

Just like it’s important for a car to function, antifreeze in tundra insects is critical for life. Insect antifreeze is a naturally occurring protein that lowers the freezing point of water in insect bodies.

The protein's structure also lets it attach to ice crystals to prevent more from forming. Not only do insects benefit from this adaptation, but arctic fish do as well.

The cold can affect insects in other ways, as some insects mature very slowly, perhaps taking 10 to 15 years to pass through all their larval stages. This slow growth occurs because they can only get a little food each short summer. No matter the size of the animal, life in the tundra can be tough.

Images via Wikimedia commons. Woolly bear image via IronChris.

Read more about: Trekking Through Tundra

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Animals of the Tundra

- Author(s): Dr. Biology

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published: 17 Feb, 2014

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/animals-tundra

APA Style

Dr. Biology. (Mon, 02/17/2014 - 18:53). Animals of the Tundra. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/animals-tundra

Chicago Manual of Style

Dr. Biology. "Animals of the Tundra". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 17 Feb 2014. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/animals-tundra

Dr. Biology. "Animals of the Tundra". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 17 Feb 2014. ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/animals-tundra

MLA 2017 Style

Animals handle the cold of the tundra many different ways. This woolly bear caterpillar can freeze solid, then thaw, and keep on living and growing.

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.