Zombie Ants

What’s in the Story?

You wake up and stretch. You feel extra tired, but your sisters are already up. You follow them along a trail through the forest, but you fall behind.

Slowing, you look for a short cut. You walk off the trail and up the nearest plant stalk. You don’t remember why you chose this plant, but you keep going until you crawl under a cool leaf. Suddenly, you find you are biting the leaf. That's when you realize you are not in control of your body.

The leaf crunches in your mouth. You try to pull away, but can’t. You are paralyzed. Not a muscle moves. Your vision blurs. A small pressure in your head is the last thing you feel before you black out.

This is not the plot of a new horror movie, but potential last moments of an ant infected with a deadly pathogen. In the PLOS ONE article, “Long-Term Disease Dynamics for a Specialized Parasite of Ant Societies: A Field Study,” researchers explore the Ophiocordycep fungus and the ‘zombifiying’ threat it poses to its ant host. These researchers learn about how and when the fungus spreads, and how ants might avoid turning into zombies.

The Spread of Spores

As you walk through the forest, you see many dead ant bodies. The bodies look twisted and a huge mushroom stalk shoots right out of each head. This is how the fungus spreads from ant to ant. It grows out of the ant, killing it in the process. The fungus then releases spores to infect the next wave of ants, turning them into zombies. How does this fungus infect ants? Let's take a look at the ants that carry the fungus. We call them the host.

The Host: Carpenter Ants

This species of carpenter ant (Camponotus rufipes) lives in South America, and is primarily active at night. These ants build very distinctive nests on the forest floor.

In ant societies the young ants generally work within the nest rearing young, processing food, and constructing new tunnels. As they age, the older ants do the riskier tasks outside the nest such as exploring, food gathering, and trail maintenance.

Ants maintain long trails, much like our roads, which they walk to collect food and other resources. All of the risky tasks, such as collecting food, are done by the older ants, which will soon die of old age. This acts as a safety net for the colony, so that they only risk losing the older individuals that have already done a lot for the colony.

The Zombifying Parasite: Ophiocordyceps Fungus

The Ophiocordyceps fungus (Ophiocordyceps camponoti-rufipedis) only infects one species of carpenter ant (Camponotus rufipes).

The fungus starts life as a spore falling down onto an ant. The spore gets inside the ant's body and grows, gradually taking over its ant host. The ant stops doing normal tasks and starts to act for the benefit of the fungus.

One day the zombie ant leaves the nest in search of a place the fungus can grow. The ant will climb up above the forest floor and bite down on the underside of a leaf in just the right conditions. There, the ant dies. But that is not the end of this story. Firmly attached to the leaf through the ant's bite, the fungus again starts to grow. A long stalk bursts out of the ant’s head and continues to develop until it forms an ascoma. This is the fungus fruit, which releases new spores to transform other ants into zombies.

Spread of the Zombie Fungus

This doesn't quite make sense. Why does the fungus-infected ant leave the nest before the fungus releases its spores? Wouldn't it be easier for the fungus to release spores within the ant nest and infect the whole colony? Is the ant exerting some last bit of free will to save her nest mates?

To answer these questions, the researchers set up nests with and without ants and added ants that had recently died from the fungusinfection. They wanted to see if the fungus would grow in the nest. If it did, would the spores infect the colony? The researchers left the colonies alone for 10 days. Then, they looked at all the infected ant bodies to see if the fungus had grown.

None of the fungi were able to grow correctly in the ant nests. Most of the fungi did not grow at all. In fact, 64% of the time, infected ants were removed and destroyed by the other ants. Those fungi that did grow never developed well enough to release spores.

The scientists concluded that the zombie ants were not leaving the nest to try to save their nest mates. Instead, the fungi led the ants to specific locations where the fungi could correctly grow and release infecting spores.

Constant Zombie Threat

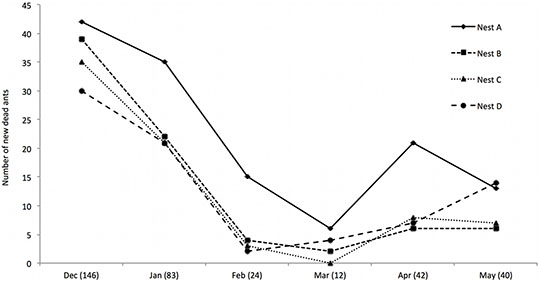

The ants can stop fungus from growing within the nest, but the fungus still kills some ants in every colony. The researchers watched 4 colonies for 7 months, and counted all of the dead ants that sprouted a fungus within a 100 m2 area around each nest. That is the same area as 4 full-sized basketball courts, over which they looked for infected ants smaller than the tip of your finger. Ant deaths varied throughout the seasons. One hundred forty-six newly infected ants died during the wettest month measured (December), while only 12 died in one of the driest months (March).

These researchers also found that dead ants appeared just about everywhere around the nests. The location of ant trails did not move away from any fungal threats.

So how can ants stay safe from ant-zombies? Well, remember the ant safety net? They only send out the oldest individuals to collect food on these trails. This means they only expose a portion of their nest to the outside world, where the zombie threat lurks around every corner.

While ants may have figured out how to avoid the spread of zombie fungus, remember this the next time you watch a zombie movie. While you may be safe and sound from zombies, some insects have to live alongside zombies every day.

Additional images via Wikimedia Commons. Zombie snail by Gilles San Martin.

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Zombie Ants

- Author(s): Christopher M. Jernigan

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published: 12 May, 2015

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/zombie-ants

APA Style

Christopher M. Jernigan. (Tue, 05/12/2015 - 14:38). Zombie Ants. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/zombie-ants

Chicago Manual of Style

Christopher M. Jernigan. "Zombie Ants". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 12 May 2015. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/zombie-ants

Christopher M. Jernigan. "Zombie Ants". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 12 May 2015. ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/zombie-ants

MLA 2017 Style

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.