A Warmer Future for National Parks?

What’s in the Story?

You are sitting down with a big, wrapped box on your lap. You can hardly contain your excitement. But you have to wait for what seems like forever before you can open it.

Finally, it's time. You rip into the present, opening it to find exactly what you wanted: your personal treasure. Whatever your personal treasure is, you probably want to protect it. You might put your treasure in a special place to keep it safe.

In the United States, many people treasure our country’s canyons, mountains, forests, deserts, and lakes in the same way a person can value their own personal treasure. But you cannot put a mountain in a bank or store a forest in a fireproof safe. Instead, the United States has created national parks to protect these natural treasures.

Sometimes setting up national parks is not enough to protect these areas. Recently, the climate in many areas in the United States has been changing. This can put many parks in danger of being changed or damaged. In the PLOS ONE article, “Climate Exposure of US National Parks in a New Era of Change,” scientists studied how climate change can affect national parks.

The National Park Service

Almost 100 years ago, the U.S. National Park Service was founded to protect natural landscapes such as the Grand Canyon in Arizona or the Everglades wetlands in Florida. Today, there are 401 protected sites. These include 59 national parks and many other important areas such as national monuments and wilderness areas.

From California to the Carolinas, these parks are each unique and are visited by people from all over the world. Since it began, the National Park Service has protected parks from direct human impacts. Examples of these impacts include building houses, mining, cutting down trees, and poaching animals. Boundaries and laws keep these human activities from happening inside of national parks.

Indirect Effects

Sometimes though, boundaries and laws are not enough to protect the parks. Recently, human activities happening outside of parks have begun to indirectly affect the parks. Indirect effects can disturb national parks even from outside their boundaries. Some of the bigger indirect effects come from anthropogenic climate change. “Anthropogenic” changes are those caused by humans.

Some changes in climate are happening because in general people are using more resources than ever before. This is creating more pollution. Even though these changes are happening outside of national parks, they can also have an effect on things inside of them. Little is known about how the indirect effects of anthropogenic climate change are impacting the national parks.

Scientists from the National Park Service wanted to know how temperature and rainfall within U.S. national parks were changing as a result of climate change. They were also interested in whether certain national parks might be more affected than others.

Big Data

Scientists used data that have been collected since the year 1901. They were interested in how climate change over the past 30 years, from 1983 to 2012 has caused precipitation and temperature to be different compared to previous years. They looked at data from 289 different protected park areas.

The data included information related to climate, like precipitation and temperature. It turns out this is a huge amount of data, especially when looking across so many years. Scientists used statistics to help them make sense of this large amount of data.

In this study, a statistical model was used to help scientists understand how the temperature and amount of precipitation changed over time. It also let them look at whether the pattern of change was the same. For example, the temperature could change slowly over many years or change quickly over only a few years.

A Time of Change

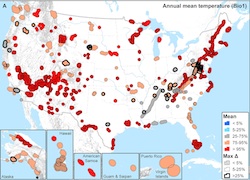

Overall, scientists found that across the United States, protected areas were getting warmer. In fact, in 235 of the 289 protected areas, they called the temperature rise extreme. This wasbecause the average temperature in these parks was significantly higher in years after 1983 compared to almost all the reported temperatures prior to that year. Only three parks had an average temperature that was colder than temperatures before 1983.

While temperatures across these protected areas were generally warmer, precipitation patterns tended to differ between sites. Parks in the southwest, like Lake Mead National Recreation Area in Nevada and Arizona, had higher temperatures and lower precipitation.

Other parks in the northeast, such as Acadia National Park in Maine, had higher temperatures but higher precipitation. Scientists thought this could be due to the location of each park.

Overall, scientists found that all parks are affected by climate change, but they are not all affected the same way. This is because national parks across the United States are diverse. Changes in precipitation will affect a dry desert valley in Arizona and a snow-capped mountain in Montana differently.

The Future of Our National Parks

Many national parks in the United States are dealing with the impacts of climate change.

For example, trees in Joshua Tree National Park in Southern California are used to living in an area with a certain temperature. As the park’s climate becomes warmer and drier in the future, the Joshua trees might not grow as well in the park anymore. Climate change caused by our own actions could hurt the trees that we are trying to protect.

The results of this study have also raised many new questions. How will plants and animals in national parks respond to climate change? Are there ways to stop the harmful effects of climate change on these parks? The National Park Service and other scientists will do their best to prepare for these changes to keep all the national parks healthy so they can be enjoyed by future generations.

Additional Images from Wikimedia Commons. National Park service image with blue background via the National Park Service. National Park Service Headquarters image from Zion National Park via McGhiever. Delecate Arch image at sunset by Misha Stepanov.

Bibliographic details:

- Article: A Warmer Future for National Parks?

- Author(s): Michelle Sullivan

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published: 8 Dec, 2014

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/warmer-future-national-parks

APA Style

Michelle Sullivan. (Mon, 12/08/2014 - 08:24). A Warmer Future for National Parks?. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/warmer-future-national-parks

Chicago Manual of Style

Michelle Sullivan. "A Warmer Future for National Parks?". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 08 Dec 2014. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/warmer-future-national-parks

Michelle Sullivan. "A Warmer Future for National Parks?". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 08 Dec 2014. ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/warmer-future-national-parks

MLA 2017 Style

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.