Spreading Stories of Sickness

What's in the Story?

You get home late from school, put down your book bag, turn on the TV, and collapse on the couch. The news starts blaring. You're about to change the channel when the newscaster announces a "breaking news" story.

In a town across the country, a child has been spotted shuffling down the street, while grunting and repeating "braaaaaaiiiiiins." Authorities have taken the child into custody to provide medical care. They have offered no comment. The newscaster closes the story with "Could this child be a real-life zombie?"

Zombies? Could there be zombies?? You run to your computer and start searching the Internet. What is a zombie? Could they really exist? Was the zombie apocalypse finally here? You call your parents and friends to see how they are reacting to the news. Finally, the news articles online start to carry updated information. The "zombie" was just a child pulling a prank.

In the PLOS ONE article "Mass Media and the Contagion of Fear: The Case of Ebola in America," scientists explain that in some situations, news stories may be driving your internet searching behavior. They find that news videos may be responsible for causing increased interest in subjects relating to the spread of disease.

When Viruses Go Viral

News can be scary. People can get sick, go missing, and cause violence. News agencies report this information on TV, websites, and social media (websites that let you share content or network, like Twitter or Facebook). But people also create interest in news. When you post information or news items through social media, you are helping the news to spread. Sometimes this can be a good thing.

The spread of news through social media can actually be thought of like a virus that you can catch. Some researchers have found this helpful. They've tried to track or predict outbreaks of the flu based on how many people talk about flu-related symptoms on social media.

However, the spread of flu information doesn't just depend on flu infections. It can also be increased by news coverage of the flu. Based on this information, a group of researchers used social media and news media to trace the spread of information related to a virus outbreak. They focused on when Ebola was found in the United States in 2014.

Ebola is bad news. There is no way around that. It's a virus that is spread by contact with those infected and that is often fatal in the animals it infects, including humans. This makes it an interesting example to use when researching the spread information on the news and social media.

Pandemic: A Trail of Fear

The infection rate increases and the virus that you and your team had limited to Africa suddenly appears in New York. None of the other players in the board game are near enough to control the infection, so you use your turn to try to move closer. As the next player reaches for a card, you get nervous. Where will the infection spread next?

The spread of a real virus isn't much like the board game of Pandemic, but each new flip of a card could be compared to the airing of a virus news story on TV. With each story, new people in new cities are infected…they catch an interest in the story, and many of them pass it on.

Social media makes this process easy. You can hear a news story and be searching the internet within seconds. In this study, researchers checked if news stories on Ebola increased related public interest or panic. The case of Ebola in the United States in 2014 was used because there was no real need to worry. Though there were four cases of Ebola, proper quarantine and treatment kept it from spreading. Three of the four people infected were well again within one month of treatment.

A Twitter of Tweets

How much and when the news spread interest in Ebola was measured by counting news stories on two major TV channels: Fox News and MSNBC. How people responded was measured by counting Internet searches (using Google Trends) and tweets (Twitter posts) related to Ebola. The search terms "Ebola," "Ebola symptoms," and "Do I have Ebola," covered a range of interest, from educational to fearful. Retweets and tweets from news accounts were not counted.

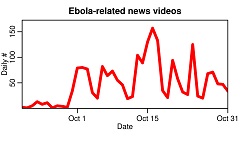

The researchers observed records of these two data sets (news stories vs. searches or tweets) for a six-week period in September and October of 2014. They analyzed each set of data using a mathematical model. It was similar to models used to measure contagion, or the spread of disease. Basically, they were treating interest in Ebola as a virus you could catch. The model also included interest in or boredom with the topic as part of the calculations.

Next, the researchers compared the data to see if the trends in news stories could predict trends in internet searches or tweet (and vice versa). For this, they used a Granger causality test. "Granger" is based on the man who discovered the test (Clive Granger). Causality is in the name because the test can be used to find if one set of events caused another.

The Granger causality test supported the idea that TV news stories caused the spread of interest (or fear) among people. The effect didn't work the other way around, meaning people's Internet searches didn't affect the number of related news stories.

Fickle on Facebook

There were only four known cases of Ebola in the United States in 2014. However, each Ebola news video that was aired caused tens of thousands of related Internet searches or tweets. What's to keep this widespread interest from driving everyone crazy with worry?

Luckily, we develop an immunity to news. Someone can easily be "infected" by the news, but they recover from that infection quickly and then don't "catch" that interest again. In this case, recovery time was around three days. Basically, some people felt the need to spread the word but then seemed to get bored of it.

This isn't always the case, of course. When more people are involved and infected from an outbreak, the interest in the disease might stick.

Power of the People

While we may make a big deal out of small issues sometimes, our interest in the news and our public use of social media can be helpful. Researchers understand this. They will continue to explore how our reactions to information can help track diseases. Who would have thought that a tweet or an Internet search could be so useful? And your tweet can still be interesting, especially to scientists. Even if it's written because of a news story about fake zombies.

Most additional images via Wikimedia Commons. Ebola virus electron microscope image by Thomas W. Geisbert, Boston University School of Medicine. Pandemic board game picture via boardgamegeek.com. Television cartoon (on PLOSable menu): "Television" by Everaldo Coelho and YellowIcon.

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Spreading Stories of Sickness

- Author(s): Karla Moeller

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published: 29 Jul, 2015

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/spreading-stories

APA Style

Karla Moeller. (Wed, 07/29/2015 - 16:00). Spreading Stories of Sickness. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/spreading-stories

Chicago Manual of Style

Karla Moeller. "Spreading Stories of Sickness". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 29 Jul 2015. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/spreading-stories

Karla Moeller. "Spreading Stories of Sickness". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 29 Jul 2015. ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/spreading-stories

MLA 2017 Style

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.