Isn't It Ionic?

What’s in the Story?

Mud is pretty dirty. It can get stuck between your toes or behind your ears, and can make your hair stand up straight. Getting dirty while making mud pies and mud castles can be a lot of fun, but parts of mud can actually be pretty useful, too. Some clays, components of mud, carry special bits of molecules (called ions) that can kill bacteria.

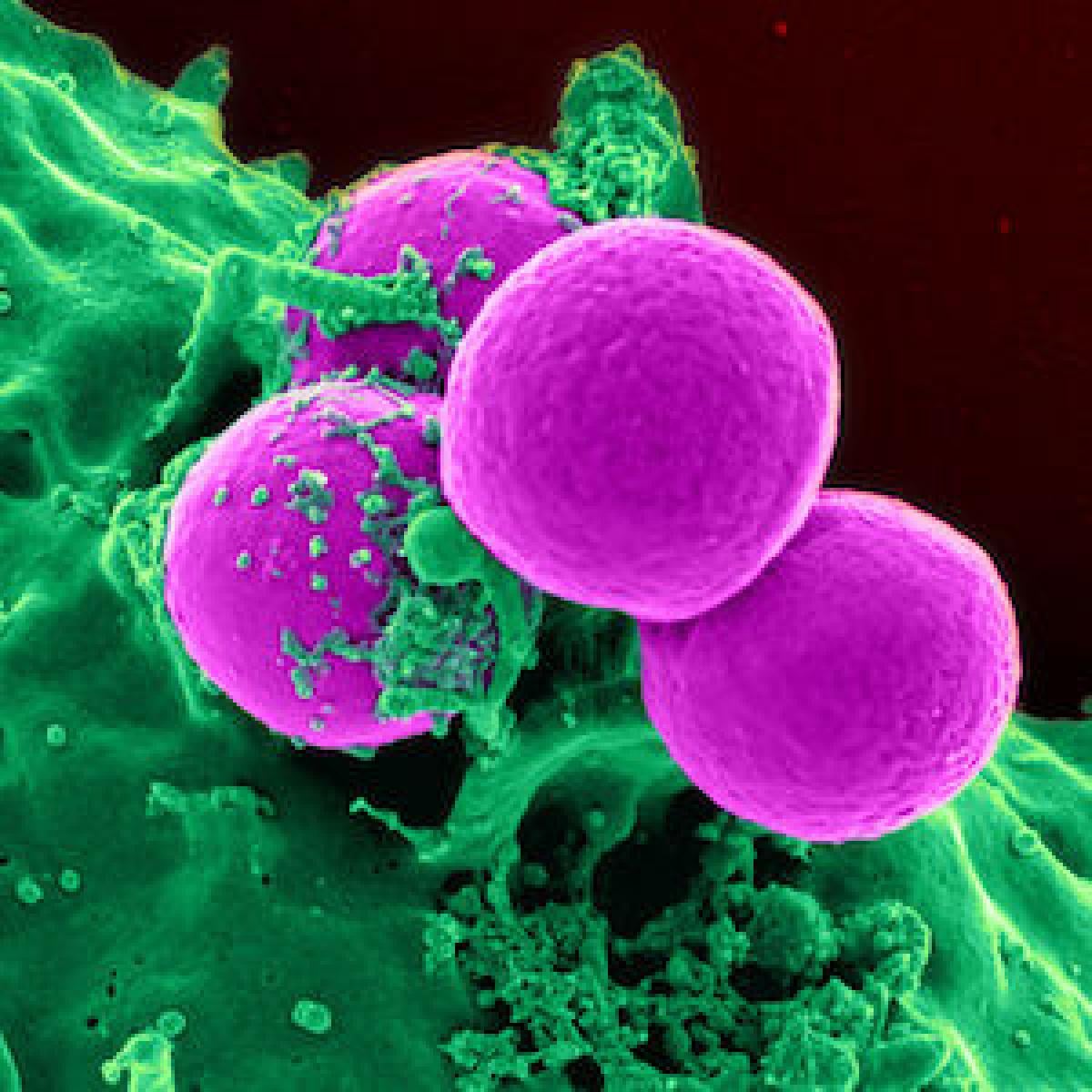

Bacteria are small organisms (we call them microorganisms) that can't be seen with the naked eye. Even so, bacteria can be found almost everywhere. In fact, your body is covered in bacteria. But there’s no need to panic, as most bacteria are harmless. It turns out that only some bacteria are dangerous and to deal with those, we use different types of medicine.

In the PLOS ONE article, “Exchangeable Ions are Responsible for the In Vitro Antibacterial Properties of Natural Clay Mixtures,” scientists at Arizona State University present their studies that show the special ions that certain clays carry helps them to kill bacteria.

Clay Day

Clay is found in soil and it exists all over the world. In some countries, it's used to make bricks for building, to make dishes to eat with, or to make art and musical instruments. With so many uses, you might wonder what this stuff is made of. If you look closely, you’ll find that clay is made up of many small particles that contain lots of minerals. The minerals in clay can come in many different combinations, which makes different types of clay.

In this experiment, scientists focused on clays that are able to kill bacteria. In particular, four special clays were picked for this study because they have killing ability against a variety of bacteria, including the bacteria commonly known as MRSA, which is pronounced ‘mer-sa’. MRSA is a very dangerous bacterium because it is harmful and hard to treat with antibiotics. Using clays that kill MRSA, scientists wanted to figure out exactly how the clay (or what in the clay) was killing this type of bacteria.

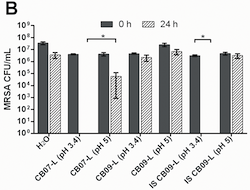

For their first experiment, scientists made mixtures of the four different clays with water and added bacteria. To see if the amount of clay had an effect on bacterial killing, scientists made mixtures that used large and small amounts of clay. Then they recorded the amount of bacteria that each clay mixture killed by measuring the amount of living bacteria left after 24 hours.

Scientists found that the amount of clay present was important to bacterial killing ability. They also found that some clay mixtures were better at killing bacteria than others. What exactly is different about the clays that lets some kill more bacteria than others? It comes down to chemistry.

Doing the "Ions" Share

The science of chemistry can explain the way things are made, how they interact with other things, and how they can change. For example, chemistry can tell us how a fire burns, or how sugar dissolves in water. It focuses on what is happening at an atomic level. Atoms are the tiny little bits of matter of which everything is made.

Atoms that have a specific charge are sometimes called ions. Ions play important roles in chemistry. In clays, a lot of ions are attached to the surfaces of clay. These ions are known to detach from clay when in water. Also, some ions are well known to cause toxicity, or harm to organisms. Knowing this, scientists wondered if the ions from the clay were killing the bacteria. Because different clays had killing abilities that were unique, scientists also wondered if clays have different ions.

To answer these questions, scientists turned to ICP-MS. ICP-MS stands for inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Say that ten times fast! ICPs create a state of matter called plasma (as opposed to solid, liquid, or gas). Plasma is ionized gas, which means it has a positive or negative charge. A good example is the gathering of charged air that can make lightning. In the lab, scientists used ICP to ionize clay samples, turning clay atoms into ions. This allowed the scientists to measure the amount and type of ions in the clay using mass spectrometry (MS).

Remember we have clays that kill bacteria at both high and low clay concentrations, and we have clays that lose the ability to kill bacteria when there isn't enough clay present. Using ICP-MS, scientists found that the major differences between the clays are the amount of five ions. These included iron, copper, nickel, cobalt, and zinc.

Ions + Low pH = Dead Bacteria

Differences in the number of ions on each clay led the scientists to their next question: are ions of iron, copper, nickel, cobalt, and zinc responsible for clay bacterial killing ability? To test this idea, scientists ran water through the clays, which let them collect water that held the ions that were once attached to the clays. This water (also called leachate) holds the same bacterial-killing ability (or lack of this ability) as the clay from which it came.

Scientists took the leachate that didn't kill bacteria and added the ions of iron, copper, nickel, cobalt, and zinc. They brought the ion levels up to match those found in the clays that do kill bacteria. However, because ion toxicity (the ability of ions to harm something living) typically involves pH, ions at different pH levels were also tested. pH is important to ions because ions can have different abilities depending on the pH level.

After this step, scientists did a similar bacterial killing test as in their first experiment. They found that increasing the concentrations of these ions gave the leachate bacterial killing ability, but only if the pH was at the right level. Bacteria killing only happened when there was both low pH and certain concentrations of iron, copper, nickel, cobalt, and zinc present. Either low pH by itself or the ions with a higher pH did not kill the bacteria.

So the next time you come across a puddle of mud, remember that hidden within all that dirtiness are special ions carried by clay. While you wouldn't want to slather mud onto a cut or other wound, scientists might be able to use that dirty mud to make some ionic medicine.

Additional Images from Wikimedia Commons via Mets501 and the National Institutes of Health.

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Isn't It Ionic?

- Author(s): Ryan LaMarca

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published: 1 Nov, 2014

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/isnt-it-ionic

APA Style

Ryan LaMarca. (Sat, 11/01/2014 - 16:02). Isn't It Ionic?. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/isnt-it-ionic

Chicago Manual of Style

Ryan LaMarca. "Isn't It Ionic?". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 01 Nov 2014. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/isnt-it-ionic

Ryan LaMarca. "Isn't It Ionic?". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 01 Nov 2014. ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/isnt-it-ionic

MLA 2017 Style

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.