Blood-sucking Science Mystery

[Bird sounds in the background.]

Dr. Biology:

This is Ask A Biologist a program about the living world and I'm Dr. Biology. You may not know it from the sounds in the background, but we're back in the studio. The sounds are from the animal that is the topic of this episode and the subject of our guest, who's been studying them for over 40 years. Now, when you spend that amount of time researching one animal, you find that you get to learn a lot about it. In some cases, you get to observe that change is part of the evolution of life. It also shows that science is not static What you find out is true at one time can change years later. Our guest today is Charles Brown, a behavioral ecologist, and professor in the Department of Biological Sciences at the University of Tulsa in Tulsa, Oklahoma. For over 40 years, he's been studying a very acrobatic bird that's also quite the engineer. It turns out it's also a survivor, even when faced with a blood-sucking villain. Charles, thank you so much for joining me on Ask A Biologist.

Charles:

Well, thank you. I'm happy to be here.

Dr. Biology:

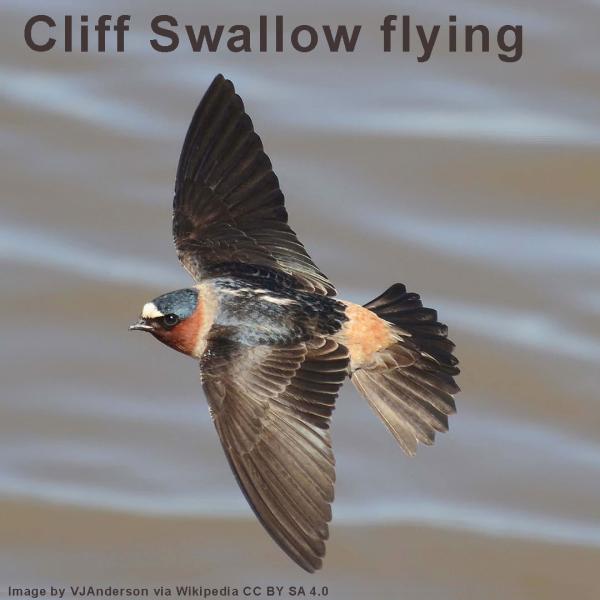

It's wonderful to have you here. It's wonderful because we're going to talk about one of my favorite types of animal, and that's a bird. And the bird we're going to be talking about is a cliff Swallow. Let's talk about these birds a little bit and what they're like where you find them, their acrobatic nature. Let's start there.

Charles:

Well, cliff Swallows are small birds. They're about the size of a sparrow. But unlike sparrows, cliff Swallows live in the air. They're very aerial, we should say. So, they catch all of their food on the wing. They won't take anything that's on the ground. They won't eat seeds. They won't even eat insects if they're on the ground. So, they have to be very maneuverable. They have to have an area that is open so that they can fly and see insects in the air and catch them in that way. Therefore, areas that have a lot of trees for instance, are not going to have a lot of cliff Swallows.

Dr. Biology:

Oh, yeah. I guess kind of getting away, wouldn't it?

Charles:

It would. Anything that obstructs their ability to fly is going to be a problem.

Dr. Biology:

OK. I'm going to ask the silly question. They're called cliff Swallows. Is that because they live on cliffs?

Charles:

They used to live on cliffs. OK, so before humans sort of came onto the landscape and started to build houses and roads, they were always on cliffs in very remote, rocky places where it would be very difficult actually, even to see them in many cases.

Dr. Biology:

And their nests aren't like a normal nest.

Charles:

That's correct. Their nests are shaped like a gourd. They're built out of mud. Each nest is maybe the size of a cantaloupe. And they cluster their nests together in large numbers. They often touch each other. So, in this way, the birds are very social. They live in very large groups. And their nests are always near others of the same species.

Dr. Biology:

How social can they get?

Charles:

We have had colonies. A colony might be defined as all of the birds on a particular bridge. We've had colonies as large as 6000 nests on a single bridge. So, the numbers vary. You can actually find very small colonies as well. And occasionally a pair of birds will live by themselves. But usually, there are three or 400 nests on any given site.

Dr. Biology:

Hmm. You said bridge. We started with cliffs. What's the thing going on with bridges?

Charles:

Bridges are basically fake cliffs so that a bridge has a bit of an overhang. And the birds can put their nests underneath the overhang. It protects from the rain just the same way that a cliff ledge would protect from the rain. So, sometimes the birds will go up under a bridge and they'll be completely underneath and this is a very safe environment from rain and wind. It may even be safer from predators such as snakes. That are able to get to the near own cliffs much more easily. So, what we've seen is these birds moving off of cliffs onto bridges. And in many places, they actually live on houses, people's houses. They will nest up under the eaves of somebody's house They're often unwelcome there because usually there are a lot of them. And people don't want that many bird nests on their house.

Dr. Biology:

Right. Especially those made out of mud.

Charles:

Correct.

Dr. Biology:

You've been doing research on this bird for a really long time. More than 40 years.

Charles:

We will be starting this summer, our 41st season studying cliff Swallows in Western Nebraska.

Dr. Biology:

OK, now, now you got me going here. Cliff swallows western Nebraska. I'm sorry. I'm going to think of the stereotypical old Nebraska flat as the eye can see. You're going to tell me. It's those bridges, huh?

Charles:

It's bridges in western Nebraska. However, parts of western Nebraska have cliffs where the birds always occurred. And we have more of them now than we had before there were bridges, but they have always lived in western Nebraska. There are parts of western Nebraska that are flat as a pancake, as you describe but there are also cliffs there, mostly along the Platte River. And the birds always use those in smaller numbers.

Dr. Biology:

So, we've got these amazing birds, these acrobatic birds that are actually engineers because of these cool nests that they build. But that's not really the story. The story has you know, if we're going to say the swallow is the hero or the main character, there's a villain.

Charles:

That's very true.

Dr. Biology:

And the villain, like you can imagine, obviously have some ulterior motives and they're not usually good motives. So, let's talk a little bit about the villain in this story. This long story. So, let's introduce the villain.

Charles:

The villain in this case is an insect that lives in the cliff Swallow nests. Now, this insect is a parasite, which means that it makes its living off another animal. Doesn't kill the other animal necessarily. But it may take blood, it may take fluids. It gets its nourishment from the other animal. Something we call the host. OK. Now, whenever you live together, as cliff Swallows do, they're highly social. So, you get a lot of nests together. The odds are you're going to encounter more of these parasitic insects. And that's one of the drawbacks that these birds have from living in these large colonies. There are more of these bugs, these insects that they have to deal with.

Dr. Biology:

So, these are swallow bugs.

Charles:

They're Swallow bugs. They're very similar to human bedbugs. So, they live in the nest. They come out at night. They bite the birds. Well, biting is essentially taking blood. They take these blood meals from the birds and then they drop off again. And they live in the nest. Once the birds leave the nest in the fall, the bugs are sort of stuck there without a host. And they will stay in the nest. Wait for the birds to return in the spring.

Dr. Biology:

These bedbugs for birds. You use the word bug and it's very interesting because a lot of people just generally call insects bugs.

Charles:

Correct.

Dr. Biology:

And that the entomologists really don't like that. Entomologists, they are the ones that study insects. So, a little bit about this is the fact that there's a little bit of a it's not a riddle, but you can say that all bugs are insects, but not all insects are bugs.

Charles:

That's very true.

Dr. Biology:

It turns out on Ask a Biologist. We have a really nice story on that. You can actually see the anatomy and how they feed. OK, so now we have our villain when they're feeding on the birds. Do they cause any problems for the adults?

Charles:

We think they do. They will take blood from the adults, and that can be bad. You have to replace that blood that you lose to the insect. And that cuts down on the energy that you might have to feed your babies. So, they do affect the adults. They affect the nestlings more so, though, because the nestlings are smaller. They're helpless. They can't preen. They're just lying there in the nest and the bugs can feed on them at will.

Dr. Biology:

Right. And we talk about preening it's when the birds take their beaks and they actually just run it down through the feathers and get rid of insects or any other kind of could be dirt or any other things.

Charles:

Correct.

Dr. Biology:

How much of an impact do the swallow bugs have on the babies?

Charles:

At least when our study started in the 1980s. We were very interested in measuring the impact that these bugs were having on the babies. And we found that the bugs had a very highly negative effect on the baby birds. They would reduce their weight and many of them would just outright die because they lost so much blood to these bugs. And it was really very surprising at the time that these bugs had such effects on the birds. You had to wonder; how can these birds persist given this high level of parasitism?

Dr. Biology:

Right. You'd think they'd all die out.

Charles:

Correct. Absolutely.

Dr. Biology:

Yeah. And you have a photograph comparing two baby birds at ten days, and we'll put this up on our chapter notes. So, anybody who wants to see this, they will see this picture. It's very interesting because just visually it almost looks like what I wouldn't say a 10th, but certainly, you know, really small compared to the birds that were not living in a nest with any kind of a parasite.

Charles:

Correct. It was a huge difference. So, we had these babies that were the same age Some of them had parasites. Some of them did not have parasites. We went in and removed the parasites by spraying a chemical on the nest and this killed off all of the swallow bugs. And that allowed us to compare how the birds did with and without parasites. And it was a dramatic difference. Again, these that did not have any parasites were healthy. They were large. They almost all survived in very stark contrast to the ones that were exposed to swallow bugs, again, many of which did not survive.

Dr. Biology:

From your lecture, I understand the birds like to catch insects and the bugs in the nest are insects. Why don't they just eat the bugs in the nest?

Charles:

That is a question that people often ask. And the reason is that swallow bugs have these very noxious scent glands. So, if you're going to be something like a swallow bug or a bedbug that sucks on a bigger animal as a host, then you better have ways of defending yourself from the host. So, they have this very foul smell. If a bird were to try to eat one, they would probably become sick from this foul, noxious scent gland. And consequently, no vertebrates of any sort are known to eat swallow bugs or bedbugs of any sort. The only things that eat them are spiders and ants, and they don't seem to care about the noxious scent glands.

Dr. Biology:

OK, well, I can guarantee you I am not going to be eating them.

Charles:

Nor I.

Dr. Biology:

It's also interesting because you talked about how social these birds are and that they build their nests right next to each other.

Charles:

Right.

Dr. Biology:

That's got to make it easier for the bugs to move from nest to nest.

Charles:

It does the bugs are able to more easily move from one nest that might have a very high concentration. If the babies die there, then those bugs might move next door. And if the nest is close by, it's easier for the bugs to move next door. So, it can be costly to have close neighbors.

Dr. Biology:

OK, so why do it?

Charles:

Well, there are advantages to living in groups that help outweigh these costs. And for cliff Swallows, the main advantage appears to be that they use each other to help find food So they eat these insects that are found in the air. But these insects are often hard to find. They're somewhat unpredictable in where they occur. So, you may have a swarm of them that's present in a particular place for 30 minutes, and then that swarm disappears. And, well, the birds have got to find another swarm somewhere. And by having neighbors, you're able to sort of use your neighbor to find where food might be at any particular time. So, they're actually able to feed more easily if they live as part of a large group than if they live off by themselves.

Dr. Biology:

Any other advantages if you're being a social bird?

Charles:

You can also avoid predators better. When you live in a group, somebody is more likely to see a predator if it's coming in at you, and then somebody sees it, they give an alarm and the whole group then can avoid the predator. If you're in a very small number of individuals, somebody might not see the predator and it might come all the way in and get you.

Dr. Biology:

Sounds like a good hypothesis and prediction what would happen, but how do they figure out it's better in groups that there are predators?

Charles:

We did some experiments in which we took an inflatable snake, which is, you know, what people will buy to put in their garden to scare away birds. And we took this inflatable snake which actually looked a lot like the bull snake, which preys on cliffs, swallow nests. And we would tow the snake with monofilament fishing line as if it were approaching a colony. And whenever the birds would see it and give an alarm, we would measure how far out from the colony the snake was seen. And we found that in the big groups, the snake was seen very far out giving the birds longer time to take defensive action. Whereas in a small group, the snake often came all the way into the colony, and nobody saw it.

Dr. Biology:

Hmm.

Charles:

So, it does show that with many eyes, predators will be more likely to be seen and farther away.

Dr. Biology:

So being social helps you find food, and it helps you protect you and your neighbors against being preyed upon by, in this case, a snake.

Charles:

By bull snakes or hawks that will also attack these birds.

Dr. Biology:

So, when we do science, a lot of people think that once you do an experiment and you get some results, that's it.

Charles:

You're done.

Dr. Biology:

It doesn't change. And one of the advantages to your work is that you've been studying these birds and these bugs for 40 years. You went back to study these birds. 35 years later, the story changed.

Charles:

It did. It changed rather dramatically. And what we had done was we just started to notice that. Hmm. There are a lot of bugs in these colonies still, but it doesn't look like the babies are suffering to the same degree that we were seeing in the 1980s when we first started doing this work. So, we decided that we needed to ascertain if the bugs were really having less effect on the birds now than they were 35 years ago.

Dr. Biology:

Yeah, let's find out.

Charles:

Let's find out. So, we had to make our observations in the exact same way that we did in the 1980s. And when we did this we looked at them the same way we collected the same sorts of information. We found that the presence of bugs has a far smaller effect now than it did in the 1980s.

Dr. Biology:

Hmm.

Charles:

So, for some reason, the birds seem to have adapted better to these bugs over time. We don't know exactly why that has happened, but it does appear to be a very useful survival mechanism to be able to persist in the face of this sort of bug parasitism.

Dr. Biology:

So, there are just as many bugs and they're just as social as they've always been.

Charles:

Correct.

Dr. Biology:

They end up with babies that are not as impacted by the bugs?

Charles:

That's correct.

Dr. Biology:

It leaves you with a new question. Why?

Charles:

Why has this happened? And we don't really have an answer. It's clear that the bugs affect the birds less. There are several possibilities that we ruled out. One was that maybe there are fewer bugs now. That would make sense. Fewer bugs less effect. Well, there are not fewer bugs. If anything, there are more bugs now than there were 35 years ago. We also looked to see are the birds may be avoiding the bugs more now than they were 35 years ago. They could avoid the bugs by staying away from nests or colonies that were infested. So, the bugs last from year to year. Avoid one of these infested colonies and then maybe you're not going to have as many bugs. Well, they don't do that either. They reuse the colonies and the nest at the same rate that they did in the 1980s. So, that isn't the case either. We also looked at how much food they were bringing back to their babies because it could be maybe they're bringing back more food now than they were 35 years ago, which could help with the cost of bugs. And we found no that they're not bringing back more food now. So, we're left with we've seen this result. We've seen less effective bugs, but we don't know why.

Dr. Biology:

Hmm. That's the fun part about science.

Charles:

It is, it keeps us constantly thinking and hopefully, we will be constantly bringing forth new ideas, new hypotheses to test, to explain the pattern that we have seen It's often easier to observe a pattern than it is to figure out why we see that pattern.

Dr. Biology:

Right? Because there can be so many reasons for it. And it's not always just one reason.

Charles:

That's very much the case.

Dr. Biology:

Even though we don't have the answer of why this change has occurred. Is there anything that you've observed? Any other things, in particular, that might be a clue of what's been going on?

Charles:

Well, one thing I'd like to point out is that the longer you study the same animal in the same place, the more likely you are to observe changes in any sort of a behavior or any aspect of the animal. And that can be for two reasons. One is that the environment is changing, and these animals have to change with the environment. The other can be that evolution is happening. The animals themselves are changing genetically in response to some factor. So, in the case of these bugs, it may be that the birds over these 35 years have evolved ways of dealing with the cost of parasitism. It may be a physiological thing. It may be that their immune systems are different today than they were in the eighties. It's really hard to say what sorts of evolutionary changes have occurred. But we have seen the bird shape for instance, change over time. The birds have shorter wings now than they did 40 years ago. Their beaks have changed Their beaks have greater hooks on the end than they did 40 years ago. So, evolution is always happening. Populations of animals or plants are always changing. We can't always know what's causing the change, but we know they're changing.

Dr. Biology:

The good news for future scientists, you've got a puzzle out there that is waiting to be solved or the next few pieces to be put in it. Charles on Ask A Biologist my guests never get to leave without answering three questions. Are you ready?

Charles:

I'm ready.

Dr. Biology:

OK. The first one is, do you remember when you first knew you were going to be a scientist or a biologist?

Charles:

I knew that I wanted to study birds when I was 11. My father put up a Purple Martin house in our backyard. Martins were attracted to this birdhouse, and I got interested in them, made observations. And it was interesting because I started to read about Martins. I read books and articles about Martins. And soon I realized that I was seeing things that no one had reported in print anywhere. So, I was making discoveries even when I was 14, 15. And that was cool. That was really really neat to realize that you were discovering things that nobody else knew. And I guess that thrill of discovery and finding out something new is what has sustained me. That's why I wanted to study birds, to become an ecologist. But the cool thing about discovering something that no one else knows is that is uniquely yours. No one can take your discoveries away from you. And whether you do it for recognition or you just do it for intrinsic interest, there's nothing like finding out something new that no one else knew about something.

Dr. Biology:

Right. Today, a lot of people will play games and they find a new way to accomplish something that they wanted to do in that game. Science is the same thing where it's the ultimate game. OK, so the next question I'm going to be cruel. I'm going to take it all away. You're not going to be a scientist. You're not going to be able to teach because almost all my scientists that come through here love teaching as well.

Dr. Biology:

What I want to know is what would you be or what would you do if you could do something different and you weren't able to be the scientist that you've been for the past 40 years?

Charles:

I have no idea. I've never thought about it. I have just never thought about it. There is nothing that even remotely interests me in the same way that science does. I've always said, well, if I wasn't an ecologist, I might be a meteorologist or an astronomer. But that's still science. So, I've never actually entertained, that question.

Dr. Biology:

You're not a secret rock star.

Charles:

No, I am not.

Dr. Biology:

All right. And the last question is for those future scientists what advice would you have?

Charles:

The advice I would have is to observe things carefully and document your observations. Even if you think that they may not be important because they may not be important right now, but they might be important 10 years from now, 20 years from now. And if we had not documented, for instance, the effects of bugs the way we had in the 1980s, we would not be able to come back here 35 years later and see this change, because biology is ever-changing, evolution is happening, environments are changing because of climate change.

Charles:

Or other reasons. So, it's important to document how organisms may be reacting to these changes, but we can't do that if we don't have observations. So, start out documenting what you see. Record it and keep it available so that maybe in 20 years somebody will find that information of great use.

Dr. Biology:

So as simple as keeping a notebook.

Charles:

A notebook. Absolutely.

Dr. Biology:

Nowadays, a lot of people have phones. You could do some things on the phone as well, but that simple paper notebook is probably the best tool you can have in your, in some cases, your back pocket.

Charles:

And it could be that having a written record is what's going to be more permanent.

Dr. Biology:

Yes, that's true. [Laughter] That is so true. Well, Charles, thank you so much for being on Ask A Biologist.

Charles:

I've been happy to be here. It's been a great pleasure. Thank you.

Dr. Biology:

You have been listening to Ask a Biologist and my guest has been behavioral ecologist and Professor Charles Brown. If you'd like to learn more about his work with cliff Swallows, we will be sure to include some links in this episode, including one to the Cliff Swallow Project. Where you can learn more about these very social birds. Now, if you listen to this program on an app that displays our chapter links and images, we will also be including images that you can see as part of the show.

The Ask a Biologist podcast is produced on the campus of Arizona State University and is recorded in the Grass Roots Studio, housed in the School of Life Sciences, which is an academic unit of The College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. And remember, even though our program is not broadcast live, you can still send us your questions about biology using our companion website. The address is askabiologist.asu.edu, or you can just Google the word ask a biologist. As always, I'm Dr. Biology, and I hope you're staying safe and healthy.

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Blood-sucking Science Mystery

- Author(s): Dr. Biology

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published: 1 May, 2022

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/listen-watch/blood-sucking-science-mystery

APA Style

Dr. Biology. (Sun, 05/01/2022 - 01:00). Blood-sucking Science Mystery. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/listen-watch/blood-sucking-science-mystery

Chicago Manual of Style

Dr. Biology. "Blood-sucking Science Mystery". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 01 May 2022. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/listen-watch/blood-sucking-science-mystery

Dr. Biology. "Blood-sucking Science Mystery". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 01 May 2022. ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/listen-watch/blood-sucking-science-mystery

MLA 2017 Style

Cliff Swallow returning to its mud nest. The nest can be constructed in as few as 3 days when building next to other nests. The shared walls speed up the process and are likely one of the reasons the birds like to build large colonies of nests. Image courtesy of Charles Brown.

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.